Chapter 4: “If you are always trying to be normal, you will never know how amazing you can be.” – Maya Angelou.

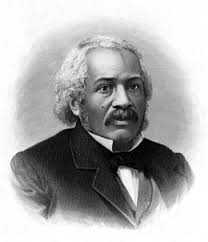

In 1837, during the golden age of the physician-scientist, ten years before Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis proposed his germ theory, African American James McCune Smith received his medical diploma. He became the first racialized Black physician in the West, the wildest dream of his ancestors. He was also the first to hold a pharmacy. He became an icon for African Europeans, like many African descendants who broke racial barriers and opened the doors for many, including me, who studied pharmacy, and my older sister, who studied medicine in Paris, France. European education taught the three of us the Ancient Greek principle of the benefit/risk balance to assess the suitability of patient treatment. Besides, the Ancestors’ Wisdom taught us that we don’t help patients if we don’t see them; we control them.

Meanwhile, in Smith’s time, European binary rationality debated whether African descendants were human based upon a century-old racial theory. Fifty years later, it would consider us and most humanity unfit for humankind undesirable: it was called scientific innovation, then. In 1787, in the USA, the first country to decolonize from Europe—at least in its dream—a trailblazing binary logic compromise counted enslaved Africans as three-fifths of a human, solving the baffling logic’s impossible middle ground. Nothing could stop European progress; one just had to force it.

James McCune Smith was born into slavery in New York in 1813, likely around the same time when a cherished child was taken from her loving family and rich culture in the Kingdom of Kongo and trafficked to the Americas. Like Smith’s ancestors, she was used as an accessory to European colonization of the Natives’ land and genocide that killed 90% of the original population and swiped the indigenous culture into the most invisible corners of the USA. It was another collateral damage or marginal undesirable effect of the best treatment to save humanity from itself, at least according to the baffling Lost Cause narrative. In the latter, the benefit-risk ratio was favorable when assessed from the physicians’ civilized objective perspective: the patients didn’t know what they were talking about in their unreliable subjective experience.

Smith attended the African Free School, an institution founded by European American elites so that African Americans “may become good and useful Citizens of the State” in case of emancipation. He was such a brilliant student that he was selected to give an impassioned speech to French General Lafayette during the American Revolution veteran’s trip to New York in 1824. Freed at age 14 by the 1827 New York Emancipation Act, his three fifths of humanity acquired immediate full citizenship. So, Smith later applied to New York’s Columbia University and Geneva Medical College (now Syracuse University). The exclusive innovative institutions rejected his outstanding application due to racial discrimination.

Determined to become a physician, Smith was accepted in the 1830s into the University of Glasgow, Scotland, a leading Western institution, thanks to European American abolitionists’ support. Unlike the free USA, colonial Britain abolished slavery in all its territories in 1834. The former enslaver empire had a relative tolerance toward Africans, although abolitionism was akin to today’s animal rights activism because of Western science classification of humankind.

Smith lived in Britain fifty years before the country invented the 20th-century purifying medicine that became humanity’s most potent poison and most . Like today, patient Smith could only survive and thrive if he renounced any little drop of Africanness that European colonization’s civilizing whips hadn’t savagely erased. Thanks to this brutal assimilative process, he didn’t have to Europeanize his name, so European descendants felt unconcerned around him, unlike many of my immigrant schoolmates in the eighties. My Asian friends had a particularly challenging time when their languages had sounds French grown-ups couldn’t pronounce, and, unlike us, pure, innocent, unconcerned, and free adults didn’t learn. Like us, Smith couldn’t be anything that deviated from today’s eugenic standards, so his uniform peers’ binary logic could say, “You are my equal.” Even the famous anti-racist and father of modern anthropology, German American Franz Boas, believed assimilation was the solution to the so-called Negro problem.

As my Kongo French mother warned me about the racialized Black experience in the West when I was a child, Smith likely had to achieve twice as much as his peers to get half as much. Besides graduating in medicine and advancing science, he spoke seven European languages, published poetry and political essays, and was an abolitionist and famous chess player. I have a doctorate in pharmaceutical science and a master’s in law, speak eleven European languages, and am a world traveler, trained opera singer, certified fitness instructor, and writer: some things never change. America calls it White supremacy; Europe calls it normality. I call it Eurocentricity: think local; act global, also known as speaking European in my multicultural family.

Because some things never change, losing perspective and straying from humanity, including mine, as highly educated eugenicists did, have been my worst fears while applying Western knowledge. When I was three years old, my Kongo father left the Christianity European colonizers forced on our family and converted to Sikhism, a Dharmic Indian religion. So, I was blessed with authentic non-Eurocentric Eastern knowledge, besides my ancestral African understanding of reality. Both are multidimensional logics. My teenager’s tender mind had no idea how to use all three when the binary logic of one claimed the two others were inferior.

In the late nineties, after Western education’s European binary system asked me to choose between perceived superior science and the inferior humanities and the half of my brain that I wanted to use. When I started college in France to study pharmacy as Smith did in Scotland as a part of his medical education, my Sikh Kongo architect father stressed that our family became Europeans while living in France. We took over European culture’s karma by following harmful traditions embedded in Eurocentric Western society. True enlightenment was the only way to break the pattern of suffering. We had to unpack this evident heavy baggage so we and our descendants no longer had to carry it. “The Ancestors also perceived it that way,” he said about Kongo Animist rationality that perceived humanity’s interdependence. He repeated the African proverb, “In Africa, we say that if we stand tall, it’s because we stand on the shoulders of many ancestors. The Ancestors give us life, wisdom, and guidance. They are like our experts.”.

My father added, “I heard European psychology does it, too, but I do not trust it. I would not entrust European scientists with my African mind. Their individualistic Western culture often fosters self-absorption. Humanity does not live in laboratories and universities’ confines. They say they know and value humankind but still ignore and devalue humans because they cannot see beyond their microscopes. I do not know what I would learn from them other than hating myself.”

Then, my architect dad recounted the cautionary tale of W.E.B. Du Bois, the famous American Pan-Africanist, civil rights and decolonization activist, historian, and sociologist. Du Bois was the first African American to earn a doctorate, graduating from Harvard in 1895.

The lauded scholar Havard-educated supported eugenics, unlike self-taught abolitionist and anti-eugenics orator Frederick Douglass. Du Bois wanted to include African descendants in breeding the budding Western middle class from the slums of Western science-based industrialization generated. Indeed, the middle class became the only option left to avoid generational poverty and self-hatred violence, as desirable, purified, indentured White women took over the breeder role from enslaved Africans to ensure a productive, wealthy society. With eugenics, women of European descent could all aspire to become blithe Southern Belles and men violent gentlemen. Then, democracy progress opened the twisted gates of this exclusive haunted club. So, Du Bois and other African American activists contributed to fostering a thriving Black middle class in post-WWII, for the best and the worst.

What about now in this update? Indeed, the revered American academic argued to his receptive European American peers that the “Negro problem” was due to “Black females’ over-fertility and poverty,” echoing the despicable prevention campaigns of the free public Maternal and Child Protection clinic in my childhood in France in the eighties. Like in Du Bois and Smith’s time, exclusive Western education was the only way to thrive in humanity in my time in the 2000s. So, while my pure, innocent, unconcerned, and free French schoolmates eyed PhDs at the most prestigious American universities, I dreaded what those selective institutions would do to my very human mind. I feared what part of my deep soul I might lose when they “included” me and invited me to develop my sharp expertise and sit on many people’s heads along with up to one-third of privileged legacy students

Smith didn’t stray from humanity. He networked with Scottish abolitionists, like John Murray, who saw him as more than their equal, meaning the outstanding human being he was. Smith became one of the most outspoken anti-slavery activists. Besides, he took residency in the gynecology ward of Glasgow’s Lock Hospital for Women, a decade before Semmelweis started in Vienna Hospital. Based on his experience, Smith published two articles in the London Medical Gazette. They became the first scientific publication known to have been published by an African descendant in a scientific journal. Exposing the unethical use of an experimental drug in non-consenting female patients, the articles aimed to save women from uncritical expertise, similar to his relentless Hungarian peer’s groundbreaking work.

After an internship in Paris, France, Smith returned to the USA in 1837, fully trained to join “the good and useful citizens of his state,” as per New York’s African Free School’s mission statement. Hailed as a hero in his Black community, he became the first African American to be published in American medical journals. His articles challenged scientific racism’s status quo and Western science’s establishment’s magical thinking. Still, Smith was never admitted to the European-American-led American Medical Association due to the color of his skin. Determined to help humans, he opened a medical practice in Lower Manhattan, treating Black and White patients. In 1847, the generous polymath scientist-physician became the first appointed physician of the Colored Orphan Asylum. He took care of countless vulnerable children and people living in poverty while continuing to fight for the end of slavery and published numerous critical essays supporting human rights.

James McCune Smith died from heart failure and, with his sanity intact, thanks to his discerning community and other enlightened intellectuals’ acceptance, in 1865, nineteen days before the Thirteenth Amendment of the US Constitution abolished slavery. He was survived by his beloved White European American wife, Malvina, and their so-called fair mixed-race children. The couple raised their cherished brood as Whites to escape racial discrimination, high unemployment, unhousing, and lynching and to increase their opportunities. They survived eugenics, Eurocentric Western science’s treatment to purify humanity: they became lawyers, businesspeople, and teachers. Smith was buried in an unmarked grave, like many parents who saved their children by passing them as White. So, his story was erased from the Eurocentric mainstream and his loving family.

Meanwhile, Smith’s remarkable achievements survived in the memories of enslaved African descendants and reached me through the African oral tradition that my father carried out. As U.S. academia evolved to welcome humanity’s authentic diversity, scholars rediscovered his noticeable achievements in the twentieth century and his descendants, their Black heritage, in 2010. The New York Academy of Medicine posthumously inducted Smith as a fellow in 2018. His alma mater, the University of Glasgow, named a new Learning Hub and a scholarship following Smith in 2020.

In African collective healing’s rationality, acknowledging invisible contributions to science and humanity’s progress is like the first step to healing from the toxicity of the uniformizing medicine a privileged, educated ultra-minority believed would save humankind. Then, magic happens, my Africanness would say: we see reality clearly. We reached enlightenment, my Asianness would reply. Meanwhile, my Europeanness stays speechless. Those silent words are the next stop in our journey in our incredible story, using African tradition because, in the latter, silence speaks louder than words.