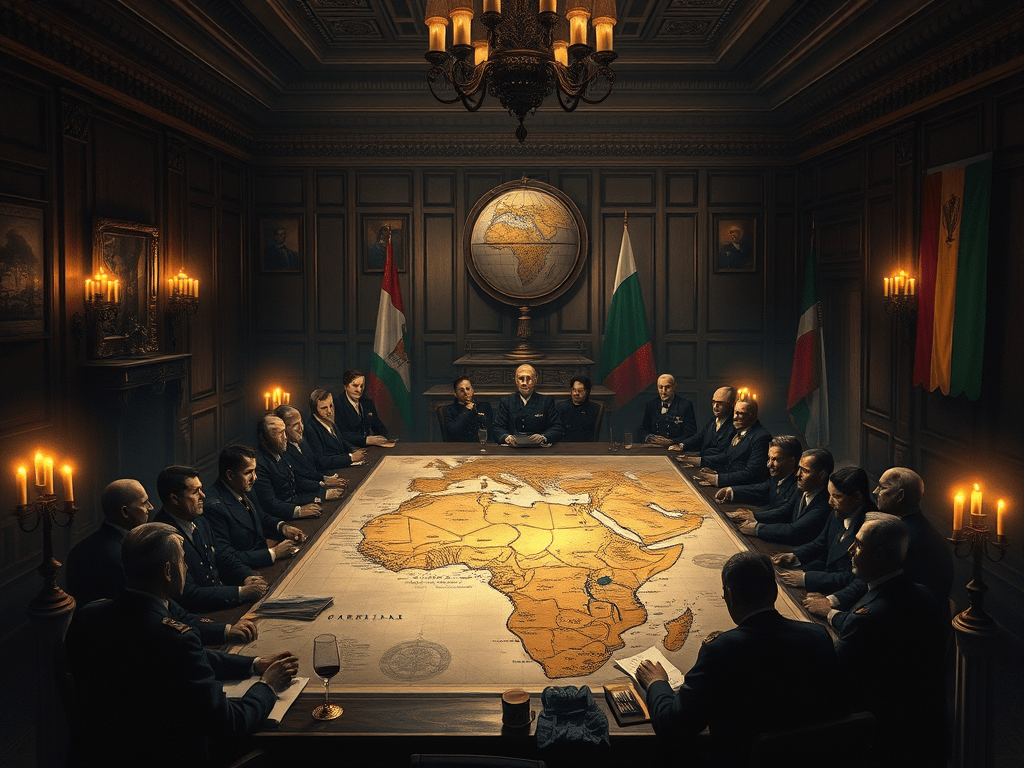

Today marks the anniversary of the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, a pivotal event that shattered the sovereignty of the African continent in the continuation of a narcissistic enterprise that aimed to transform the world so it could reflect Europe’s grandiose image. In this room of imperial powers, European elites decided to discover Africa as Columbus discovered America almost 400 years before. They carved up the so-called Dark Continent without a single African voice present to exploit the resources of the richest continent in the world at the source as transatlantic slavery (1501-1888) became less profitable. This brutal divide fueled a continuous legacy of exploitation and dehumanization that continues to reverberate through generations after Africa’s independence that spanned from 1951 in Italian colonized Lybia to 1991 in Apartheid South Africa.

In my Kongo family, our oral tradition calls the European business model of colonization of Africa “exploiting Africans at the source.”

One of the darkest chapters of this legacy unfolded in what is now Namibia under German colonial rule. Between 1904 and 1908, the Herero and Namaqua people faced extermination in what many scholars recognize as the first genocide of the 20th century. The architect of this atrocity was Heinrich Göring, the father of Hermann Göring, a key figure in the Nazi regime. In these concentration camps, racial science was born—a pseudoscience that would later underpin the Holocaust. The skulls and bodies of murdered Africans were shipped to Europe, where scientists used them to “prove” the inferiority of African descendants with dark skin.

The Birth of Eugenics

Eugenics, a so-called “science,” was born from these colonial atrocities in England in 1887 from the polymath brain of Sir Francis Galton, a statistician still celebrated today. The twisted science sought to classify humanity into a hierarchy of worth based on race, physical traits, and perceived mental capacity. It promoted selective breeding to “improve” the human race by eliminating traits deemed undesirable—often targeting African descendants, Indigenous peoples, and other marginalized groups like humans with disabilities, those living in poverty, and shockingly, patients with perceived undesirable diseases, like epilepsy. This ideology was foundational to Nazi racial policies in Germany, the aspirational global leader in Western science pre-WWII, but also shaped medical and scientific practices across the globe, including in the United States and Europe.

While recounting this soul-shattering story, my father’s voice still echoes today, ““If Germany had self-reflected, addressed, and repaired its actions in Africa, it would have spared so many lives in Europe later.” I can only concur.

The Weight of Today

The repercussions of these appalling actions are still felt today. African descendants face systemic biases in healthcare and science. Trust in medical institutions remains fragile, especially when these institutions have yet to reckon with their colonial and eugenicist histories fully.

Here are just a few examples of how this legacy manifests in medicine:

- Health Disparities: African-descendant patients often receive less pain management than European-descendant patients based on the false belief that they have a higher pain threshold. This bias has roots in racial science and persists despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. The maternal mortality rate among African descendants is alarmingly high, with racialized Black women in the U.S. being three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than their European descendant counterparts.

- Unethical Medical Experiments: One striking European example is the “Human Zoos” that existed well into the 20th century, where African individuals were displayed in cages as scientific exhibits. In Belgium, under King Leopold II’s brutal regime in the Congo, African men, women, and children were subjected to horrific abuses, including medical experiments conducted by colonial scientists. These experiments were often justified by eugenicist ideas and had little regard for the consent or humanity of their victims. Additionally, in Nazi Germany, racial science was directly influenced by colonial studies and eugenics, leading to inhumane medical experiments on marginalized groups, including Africans living in Europe.

- Dismissal of Traditional Knowledge: Traditional African medical practices, which have been used for centuries, are often dismissed as unscientific by Western medicine. Yet, many modern pharmaceuticals are derived from plants long used in African healing. Instead of collaboration and respect, Western science frequently appropriates this knowledge without credit or reinvestment in the communities that sustain it.

For patients of African descent, colonial and generational trauma can run deep. Since my Kongo family ran away from transatlantic human trafficking in the 1800s, no generations has been born in the same place as their parents. My refugee parents witnessed their dear family and beloved friends dying in the colonized French Congo in unethical medical experiments in the name of Western science progress.

Today, many of my uncles and aunts are physicians, and some are even investigators in medical research. Still, they often warn us against participating in medical research because they can see that their colleagues haven’t done enough to address deep-rooted, invisible historical biases. “If they do not see me, how do you think they can you?” they said. Their authoritative protective voice becomes our oral tradition carried from one generation to another until one of us perceives profound, systematic changes and changes the narrative. As a scientist, doctor in pharmaceutical science, and one of the traditional authorities in my generation, I can certainly say it won’t be me. I’m still addressing my colonial medical trauma, and the Western healthcare system is poorly equipped to help me. So, like many other African descendants, I have to figure it out on my own and share my experience and findings often through our oral tradition because there is so little space for them in the Western culture.

A Path Forward

To break this cycle, we must first confront the history that brought us here. This involves more than acknowledging the atrocities of the past; it requires dismantling the structures that sustain colonial ideologies. Most of humanity has been systematically exposed to Western science’s harmful theories and/or practices. As a drug regulatory executive, if a toxic medicine still harms humanity today, I know any health authority would ask scientists and healthcare professionals to remove it. This action is called science decolonization.

Science decolonization can address different points:

- Education and Accountability: Institutions must teach science’s colonial and racial history. Scientists and healthcare providers should undergo training on bias and the historical context of their fields. Healthcare professionals and scientists trained in inclusive trauma-informed care, knowledge, and communication as a standard to address systemic abuse.

Even today, I still hear my scientist peers rationalizing that European colonization was “bad” but also had benefits, oblivious that their uneducated voice echoes the so-called European civilizing mission that rationalized the abuse of most humanity.

How much of science progress writes off genocides, mass murders, systemic death by exploitation, mass rapes, and systemic thefts? What is an acceptable threshold? I bet some reality-blind scientists cannot see the problem in investigating this humanely unanswerable question and doing what they do best: generating data, analyzing, and concluding. - Effective Diversity and Inclusion: It’s a topic close to my heart and worth more development. Western science’s abuses happened in an echo chamber blind to humanity’s reality, as the story of the scientific progress “gained” during the genocide of the Herero and Namaqua under pre-Nazi German colonial rule in Africa. In this context, we can understand how critical it is to include human diversity in each steps of the process of generating, from leadership, to implementation and results assessment. Diversity and Inclusion is not about to continue to try to save the people European culture “civilized,” it’s about to save Western science.

A couple of years ago, my chilling bones heard a group of scientist peers of monocultural European descent proudly announce they had found an innovative way to collaborate by assimilating patient data in scientific protocols. Yes, assimilation, like the colonial system, asked my African parents to do to comply with colonial reality. In contrast, when educated in science decolonization, we understand how to respect patient reality by seeking feedback in each step while co-creating science.

Diversity and inclusion are practical innovations when we can reach co-creation. It helps the team to think outside the box, provided they are educated in science decolonization. Then, we might see that Western science’s discriminative approach and binary logic of validation and invalidation is dehumanizing per design. Yet, Science with a capital S aims to be universal and objective. It’s an ideal reached by working against reality like scientists must thwart gravity to create innovation to colonize space. It’s an ideal when we generate reality-blind, evidence-based data in medicine to claim objectivity. It’s an ideal every time we create science in our labs’ hyper-controlled environment for result reproducibility and claim universality. Nothing is farther from reality than an ideal, like the one a privileged ultra-minority had when it tried to transform our planet into Europe 2.0 more than 500 years ago.

When educated in science decolonization, we might understand how reductive, limiting, and often unfit Western science’s binary discriminative logic is to address the world’s natural diversity accurately. We can see how statistical science contributed to marginalizing realities experts didn’t perceive as normal as statistician Galton, the father of eugenics, did. We might remember how much Western science is only a cultural European tool to help experts process and simplify a rich reality. We might hear that that sentence “eradicating cancer” or another life-threatening disease might reflect the same totalitarian expert-centric logic that forced Western science into other cultures. We might admit that in a multidimensional inclusive logic, there is a reality where what we call Science with a capital S is European ethnoscience, like any other indigenous knowledge. Then, we might be humble enough to acknowledge it hasn’t replaced God, as many scientists uneducated in science decolonization proclaim. Only our magical thinking believes it.

So each time we, scientists, create something out of those Western science’s reductive principles, we might check the reality we discriminated against and invalidated because it’s where authentic human-centric innovation lives. It’s visible to those who inhabit the invisible reality that Western science created centuries ago when it decided to invalidate most humanity. For example, the relentless fight for emancipation and inclusion that the uprooted enslaved Africans and their descendants led in the USA was instrumental in including humanity’s diversity in medicine. Perceived the last in humankind, they were the first to understand that including humanity is a real science. They were often the first to address biased Western science and harmful medical practices. In my family’s oral tradition, we often say that after the brutal erasure of their ancestral culture, they have no choice but to belong. They will fight tooth and nail because “American” is their only identity. Making real science is to join them and the rest of humanity. - Centering Indigenous Knowledge: Embrace and acknowledge traditional Indigenous medical practices and knowledge systems beyond the European ones that lead to Western science. Science should not be a one-way export from the West but a global dialogue.

I was raised with African and Dharmic science and educated in European ethnoscience. So, I learned inclusive multidimensional thinking from the two first and discriminative binary logic from the third. Unlike my monocultural European descendant peers, I use my three logic according to the nature of the problem I want to resolve. Asia helps me to see the big picture my scientist peers don’t see when they try to answer how much dehumanization is worth Western science’s progress. It leverages the power of the WHAT. Africa helps to hear the silenced voices of humanity’s collective subconscious: it unearths and transforms meaningful facts into human-centric narratives. It’s the power of the WHY. Then, Europe’s binary logic helps me to validate or invalidate the details: it fine-tunes reality. It’s the power of the HOW. When individuals are enough self-aware and culturally aware for co-creativity, it’s the power of the WHO.

Yet, after the European colonization, one culture believed it best to find the what, why, and how with one unique logic. American culture calls this belief White supremacy. In my multicultural Sikh Kongo family, we call it Eurocentricity. Europe calls it normality. Even today, many Western scientists dismiss non-Eurocentric knowledge as magical thinking while seeing no issue in believing that holding the supreme tool of Western science transforms them into objective beings.

So, I’m grateful I work with so many colleagues of European descent who are curious beyond the historical reality they were taught and reflect about how to decenter Whiteness as the Americans say, address Eurocentricity as my family says, or embrace a human-centric approach as my enlightened peers of European descent see it. Decentering and recentering humanity’s reality is about to find our common balance after centuries of colonial extremism and dehumanizing historical European supremacy. - Empowering Indigenous Research: Invest in African-led research and healthcare systems, ensuring that solutions are locally driven and not dictated by external powers.

The myth of the European in shining armor saving “uncivilized” humanity on his White horse is still deeply ingrained in science. Physicians from the global majority have many stories of non-diverse Western NGOs coming with brand new life-saving machines that failed after the self-satisfied saviors left because the technology is unfit for non-Western climate or not fit to be used outside Western habits. Repairing the technologies often requires expertise only available in the West, which creates a vicious circle of dependence. The latter can only be broken when Western knowledge learns to empower indigenous solutions that don’t sustain colonization thanks to science decolonization education in the West. - Restitution and Reparations: Return stolen artifacts, human remains, and wealth. But also addresses the systemic inequalities that still burden African descendants and people that Western science helped to marginalize after a powerful ultra-minority decided to colonize Africa.

In my family’s oral history, we often say that if all the medical aid the West sent to the Global majority to continue to perceive itself as the world savior was put into repairing the twisted reality it created, there would be so few problems left that it would feel useless. That’s maybe why, deep down, it’s so slow to change, because losing this ideal is like an identity for Science with a capital S. So science as we know it might lose itself when it steps into humanity’s reality, and scientists become humans again. It mightn’t be a bad thing, but as one of my managers told me one day, we need to let the parts that don’t serve us anymore give space to those that do. Then, the whole is called transformation, and change is what Western science is about.

The Berlin Conference was not just a political event but a scientific one, shaping how the world views Africa, its people, and humanity. As we remember this dark chapter, let us also commit to transforming science and medicine into tools of healing and justice.

Today, I reflect on the loss and resilience of African descendants and all those who endured European colonization. The fight for equity, respect, and humanity continues, and we owe it to ourselves and future generations to demand better. In honoring our ancestors’ stories, we reclaim the power to transform science and global health into tools for justice, healing, and humanity.